[#003] Typical Meteorological Year: From Average Weather to Climate Resilience

Typical Meteorological Years (TMYs) condense decades of climate data into one representative year. This article explores different TMY approaches and references a paper on TMY-NO method, using reanalysis data and seasonal weighting.

![[#003] Typical Meteorological Year: From Average Weather to Climate Resilience](/content/images/size/w1200/2025/11/tmy_temperature_generic-1.png)

As climate change reshapes local weather patterns, engineers and modelers need reliable datasets that capture not just the past but also plausible futures. One such foundational tool is the Typical Meteorological Year (TMY). This article will explain the advantages and advocate for wider application of this concept, including in risk management.

A TMY is a comprehensive dataset containing hourly weather parameters for a single year. Such TMY data is typically compiled from extensive historical records, typically spanning 10 to 30 years, to represent the average or typical weather conditions for a specific location. Unlike actual yearly weather data, a TMY provides a standardized and representative weather profile.

TMY data is traditionally utilized in building energy simulations, the design of renewable energy systems, and climate impact assessments. It empowers engineers, architects, and researchers to accurately predict performance, optimize designs, and make well-informed decisions by accounting for realistic meteorological variability without the arduous task of analyzing decades of raw data.

Advantages of Typical Meteorological Year in Modeling

The application of a Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) in climate and economic modeling offers significant advantages.

Better visualization One of the primary benefits of employing a TMY is the better visualization it provides. By representing a full year of typical weather conditions in a concise and manageable format, TMY data allows researchers and stakeholders to more easily grasp the general trends and patterns that influence climate and economic systems. This simplified yet representative dataset makes it easier to:

Identifying critical periods While a TMY represents typical conditions, it can still highlight important seasonal variations and daily cycles that are crucial for understanding energy demand, agricultural yields, or water resource management. And instead of scanning through multiple years of data, it0s easier to analyze one year of data obviously.

Better impact identification by calculating FMYs By developing a Future Meteorological Year (FMY)—a modified TMY reflecting projected climate changes—it becomes significantly easier to visualize anticipated shifts in parameters like temperature, solar radiation, humidity, or wind speed due to climate change. This direct comparison between TMY and FMY allows researchers, engineers, and policymakers to better comprehend, quantify, and prepare for the effects of a changing climate on energy systems, building performance, and environmental design.

Improved Performance due to One-Year Compacting Using TMYs significantly reduces computational load by condensing decades of weather data into a single, representative year, enabling faster simulations, more complex models, and quicker design optimization. This approach also leads to lower data storage requirements compared to managing extensive raw meteorological data. The data reduction factor is approximately n:1, where n is the number of years represented—often 30 or more—resulting in substantial computational savings.

More Flexibility and ease of Scenario Analysis While a TMY represents typical conditions, it's straightforward to modify specific parameters within that single year to analyze different scenarios. For example, you can easily adjust temperature profiles to study the impact of climate change, or modify solar radiation to assess different shading strategies. This targeted manipulation is far more complex and time-consuming when dealing with multi-year datasets.

Calculating Typical Meteorological Years (TMYs)

Calculating TMYs is a more intricate process than commonly assumed. Contrary to a statistical approach involving averages, as one might expect, current TMY algorithms employ an empirical method.

At the core it’s a two step process. The first step involves selecting individual months from various years within a given data period. For instance, consider a dataset spanning 30 years. Each January from these 30 years is analyzed, and the one deemed most typical is chosen for inclusion in the TMY. This process is repeated for every other month. The 12 selected typical months are then concatenated to form a complete year.

The second step addresses potential discontinuities that arise from adjacent months being selected from different years; the month interfaces are smoothed for a six-hour period on each side. Physical inconsistencies, like correcting the dew point need to be addressed also in this smoothing process.

Popular TMY variants

The Sandia Method, developed by Sandia National Laboratories, is one of the earliest and most influential approaches for creating TMYs, particularly aimed at solar energy applications. It uses the Finkelstein–Schafer statistical technique to identify representative months from long-term weather records but places greater weighting on parameters critical to solar system performance, such as solar radiation and temperature. By emphasizing these key variables, the method ensures that the resulting synthetic year accurately reflects typical solar energy conditions at a site. Although later methods like TMY2 and TMY3 refined and expanded upon its framework, the Sandia Method remains foundational in the evolution of TMY development, providing a robust statistical basis for modeling solar energy system performance.

The ISO Method, defined in the international standard ISO 15927-4:2005, provides a systematic and standardized approach for generating Test Reference Years (TRYs) and Design Reference Years (DRYs) used mainly in building energy performance analysis. This method can produce both typical years for average performance assessments and extreme years for design and stress testing, making it versatile for applications in HVAC system design, thermal comfort studies, and climate-responsive architecture. Its strength lies in its international consistency and flexibility, though it requires detailed and high-quality meteorological datasets for accurate results.

Evolution of TMY Generation: From Station-Based Data to Reanalysis Datasets

Historically, TMYs were created using observed data from weather stations, often spanning several decades. However, this method has limitations. Station-based TMYs are restricted to locations with long-term measurement sites and may not accurately represent broader areas, particularly in complex terrains that might have significant changes on the local climate.

Reanalysis datasets offer a more appealing solution for generating TMYs. These datasets provide continuous, multi-decadal weather information across vast spatial areas by integrating observations into weather models.

Looking ahead, integrating TMYs with future and extreme meteorological years (FMYs and variants) can strengthen our ability to model risks, plan resilient infrastructure, and design sustainable energy systems in a changing climate. I think we climate data scientists should use this concept more in the future.

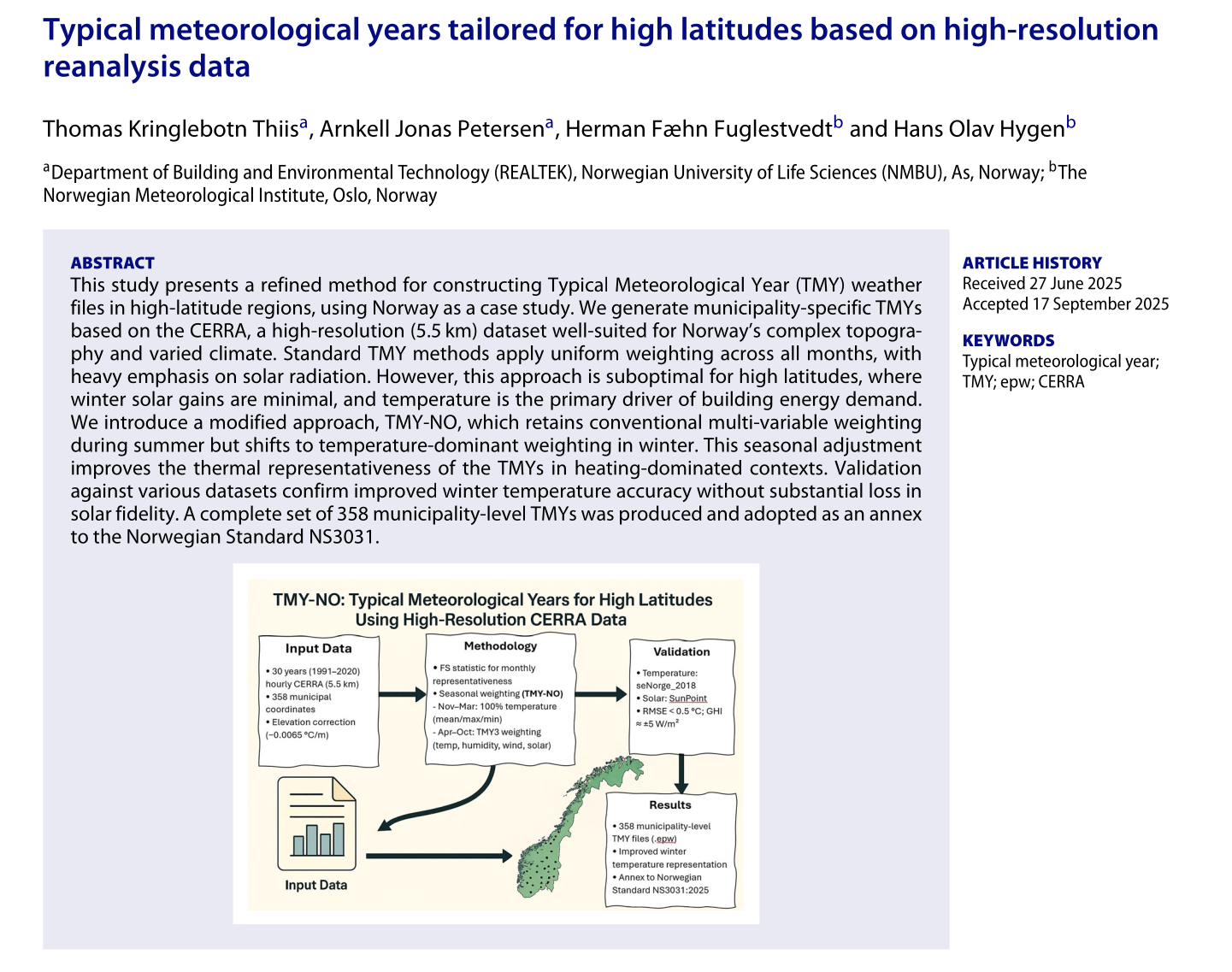

Typical meteorological years tailored for high latitudes based on high-resolution reanalysis data

This blog article was inspired by Thiis et al. (2025), “Typical meteorological years tailored for high latitudes based on high-resolution reanalysis data,” published in the Journal of Building Performance Simulation. In that paper, the authors introduce TMY-NO, a modified method for constructing TMYs adapted to Norway’s high-latitude climate. The TMY-NO approach builds upon the standard TMY3 methodology but adjusts the weighting of meteorological variables seasonally. During the summer half-year (April–October), it retains the standard multi-variable weighting of TMY3, which balances solar radiation, temperature, humidity, and wind. However, during the winter half-year (November–March), when solar radiation is negligible, the weighting shifts entirely toward air-temperature indices—40 % mean, 30 % maximum, and 30 % minimum temperature—while setting solar, wind, and humidity weights to zero. This seasonal weighting scheme corrects the bias of traditional TMY methods, which can over-emphasize solar radiation even when it contributes little to energy balance in dark Nordic winters. Validation against high-resolution CERRA reanalysis data showed that TMY-NO improves the accuracy of winter temperature representation without compromising solar fidelity in summer, making it a robust method for heating-dominated, high-latitude climates.

Read the full article on Taylor & Francis Online →